Transcript

00:00

When the towers fell on September 11th, Marty Ross Dolan was standing in her bedroom in Albany, watching the news with her young children downstairs. She had spent her whole life working towards a career in psychiatry, but in that moment, something inside her said it was time to let go. In this conversation, Marty shares what it was like to walk away from the identity she had built since childhood and discover a new one through writing, motherhood, and the long work of facing multi-generational grief.

00:28

This is a story about listening to the quiet voice inside and realizing you're allowed to change your mind. And I just knew at that moment that things were going to change for me. But I just knew that something was that something was changing. I was not all of this sort of sense of feeling torn about wanting to have more time with my kids was.

00:54

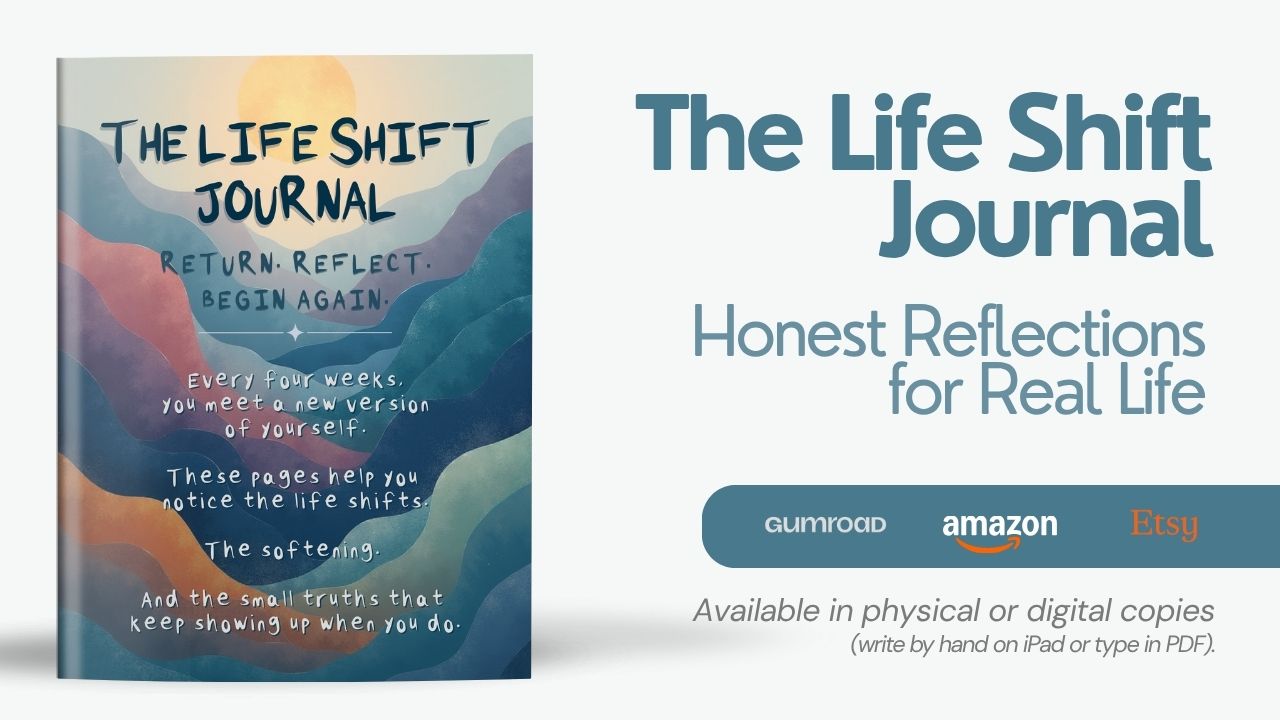

just had been rumbling in the back of my head, but it was screaming at me while that was happening. It was the beginning of saying goodbye to this specialty and this career and this practice that I had devoted really my life to. I'm Maciel Houli, and this is The Life Shift, candid conversations about the pivotal moments that have changed lives forever.

01:31

Hello, my friends. Welcome to the LifeShift Podcast. I am here with Marty. Hello, Marty. Hi, Matt. How are you? I'm good. I'm also tired. There's a couple things. We can be two things at once, right? For sure. Absolutely. Well, thank you for wanting to be a part of the LifeShift Podcast. I just never knew that I needed to hear all these stories because when I was a kid, I was visiting my father. My parents were divorced. We lived states apart from my father and I was visiting him. And one day after summer camp, he pulled me into his office.

02:01

and he had to tell me that my mom had been killed in a motorcycle accident. And at that moment in time, everything about my life and everything that we had kind of imagined for me growing up was like no longer possible because my primary parent was gone, the woman I live with all the time and was just gonna visit my dad every once in a while. I was gonna have to move to a new state. I was gonna have to leave all my friends, all my family, my school, everything about my life kind of shattered in that moment.

02:29

And this was like, the time period was late 80s, early 90s, so nobody was talking about grief. And kids are gonna bounce back. And so I saw the adults around me who also did not agree. I saw them realize that they wanted to make sure I was happy. So I absorbed that and like never, I just pushed it down and didn't really get to grieve. And I say all that because behind the scenes in my messy 20 years of trying to grieve my mom,

02:57

I always wondered, do other people have these line in the sand moments from legit one second, everything is different? And so now I'm on this exploration of talking to all these people about these similar type moments, whether they're traumatic and external, or they're like an internal fire that someone woke up one day and they decided to change everything about their lives. And so thank you, before we even get to your story, for just.

03:24

being a part of my healing journey through this podcast. Well, thank you for inviting me to be and I'm very grateful and honored. I think I knew before having these conversations, I think I knew like on the surface, the power that our stories have, both from telling it like to other people, but listening to other people's stories. And you and I were talking before recording about how it's also amazing how

03:50

we connect to maybe the weirdest parts of other people's stories, not the really ones that we put out there as the most significant parts, but people connect to the little tiny moments. And I just love that connecting the dots there. Right, right, right. Yeah, the best part of telling my story has been really the discovery of how universal experiences that feel so personal.

04:20

really are. That has been just a gift. It's funny because you're like, I could not imagine going through that yet. The way someone describes how they were feeling in the moment or how they process something, you're like, I can relate to that. Even though our experiences are so wildly different, which is a good thing. Yeah. So the human thread is they say it's very cliche that we have a lot more in common than we have that separates us. And it seems to be true.

04:49

So I guess this is the hypothesis we're proving here through podcasting. So before we get into your story, maybe you could tell us who Marty is in 2025. Like, how do you show up in the world? How do you identify? Well, now I identify as a recently published author of a memoir. Thank you. I also strongly identify as a retired psychiatrist.

05:14

probably my biggest strength in terms of identification is as a mom of two young adults. So I'm empty nested, but very, very active parent. live in Columbus, Ohio, and I'm teaching writing, teaching memoir, and sort of discovering in many ways a new sort of exciting career. Congratulations on the book release. you.

05:41

I've heard it's a long endeavor for many people and it's not quite as simple as opening your laptop and typing out a bunch of words, is it? No, my book was 14 years in the making. It was definitely not as simple opening the laptop and it required those 14 years. It was not going to happen any faster or any earlier. So that's for sure. And I bet you've learned a lot about your journey by kind of reflecting on it in this way and putting words to it.

06:10

100%. I learned so much writing my book and I'm really in very many ways a different person having written it between both the healing process of writing and also the process of re framing how I thought about past stories. And that only I think can come through writing. would I would venture to add podcasting to it. It's funny because I'll listen to my first

06:37

Well, don't anyone else listen to the first couple episodes, but I'll listen to how I tell my story and the words that I choose and how I've kind of unfolded things years later, even though, you know, my mom died 36 years ago next week. It's interesting how in the last couple of years, I found different words and different attachment and meaning through talking. So I would imagine it's very similar to the writing process of kind of like admitting things.

07:05

That's fascinating because really it's using words, right? They're both practices of using words. So why are they really that different? But so so I think I think what you're saying is would be very true. That's like journaling. changes people's lives. So I would imagine writing a memoir is a big, deep, deeper version of that journal. So congratulations to you on releasing that. No, it's big feat. And we will definitely have that. talk more about it at the end and we'll we'll have a link in the show notes.

07:34

And since it's a memoir, it's all about your story. So I'm wondering, however you want to do this, however you want to paint this picture to kind of like the before Marty that led to this version of Marty, how do you want to paint the picture of your life leading up to your life shift or or or the before version of Marty? Yeah, the the before version was a person who for as far back as I can remember, wanted to be a doctor.

08:03

My father is a physician. I'm very close with him and I also am a product of divorce. But that's where my interest was always, science and also psychology, human behavior. And I really knew that I was drawn to psychiatry as a field. And I mean, when I say like, I have an autobiography that I wrote when I was in fourth grade that said that I was going to be a doctor.

08:32

Then I was gonna be a neurosurgeon, that changed. yeah, and then, know, high school, AP biology, preparing for college, went to college because I loved the science building and wanted to be, and I was pre-med and then went to medical school specifically to be a psychiatrist. I was very driven, went straight to training. 30 years old, I had done nothing except prepare myself for that career and finished training at 30. I also had my first

09:02

child at 30. I went to medical school and I trained in New York City. And then I had my son, I had my son while I was, just before entering my fellowship in child psychiatry. And then I worked for, I believe it was two years now, I'm starting to question myself, but I think it was two years. I was director of the child psychiatry crisis service at Columbia Presbyterian in Washington Heights in Manhattan.

09:31

and taught medical students and was taking my son every day to daycare that was uh available through the hospital around the corner. My husband and I just had a routine. He was also training at the same place in his specialty. And then when he completed his program, we decided to move um upstate to the Albany area of New York. And...

09:57

ah I was at that time, I was pregnant, we moved, my husband took a full-time job and I took a part-time job in psychiatry. I was challenged, I was feeling challenged to figure out how I was going to make these two things work, having little kids and having this sort of starting a career at that point. And so- That you've worked your whole life for. Exactly. I should say that-

10:23

I said that all my life I had wanted to be a doctor. There's one other thing that I also always wanted to be, and that was a writer. But I would write when I had time, creative writer, but it was not where I could spend, I didn't have much time, and so I wasn't able to do a lot of it. I took a job when we moved to upstate New York that was a part-time job at the medical center.

10:52

It sounded good, but it wasn't going to work that well for me. It was really that I would work at the hospital. would teach work with residents, supervise residents and medical students, do some clinical work. But mostly the most important thing was that I needed to be available six weeks of the year to cover the other child psychiatrist when he took vacation. So when you have that kind of job, you just don't have that much control because you don't know when that person's going to take vacation.

11:22

So I ended up putting my, you know, and my daughter was born, so I had a baby and a toddler, and I was having to have childcare for them, even though my work was so irregular, my schedule was so irregular. And I also had started a private practice, which was picking up and getting busy, and I had a number of patients in my private practice.

11:50

I always was feeling torn. All parents feel torn when they've got little kids or even older kids and work. It's the age old sort of balance challenge. It was starting to wear on me more and more. And I was feeling more more drawn to want to just be home or just want to spend more time, have more time with my kids and not having them.

12:18

So I ended up actually moving them out of daycare. got, we did hire a nanny and I had them going to preschool. And this was, this allowed for some more flexibility and it was a little better. Then I will, I remember as we all do who were able to remember things, have memories from this time, September 11th, 2001, when 9-11 happened.

12:47

On that morning, we had been in uh Albany for about two years. I remember my kids downstairs with the nanny. Actually, my son I had already taken to preschool. My daughter was home with the nanny. And I went and got my son from preschool and brought him home early. And then was in my bedroom upstairs getting ready for my day.

13:13

My kids were downstairs with me and I was watching TV and I watched everything unfold. I was on the phone with my mother-in-law. We were sort of in shock, what's happening? And I remember seeing the towers fall on TV. And I remember telling myself, you know, sometimes we have those experiences where we see things.

13:38

and our eyes are seeing something, but our brains aren't registering it or telling us that this isn't real. And that's what was happening. I was watching it and I was thinking, but this isn't really happening. Like this is, not, those buildings aren't coming down. That's just like, it just, couldn't, it was literally a disbelief. And I just knew at that moment that,

14:07

things were gonna change for me. I had a friend who was actually, at the time he was training in the hospital at NYU and I was on the phone with him and he was watching it outside his window. And I was thinking about all the people that I knew in New York and whether or not I knew anybody who was there or they knew anybody who was there. For those of us of a certain age, this was our peer group.

14:36

in these, I mean, lots of ages were in these buildings. And I also thought about the fact that, you know, I had just finished with this job and crisis in child psychiatry and crisis right in the same city and what was happening with that, you know, how was that power? And the truth is that disaster psychiatry became its own subspecialty or its own field.

15:03

It's not a subspecialty, not something that you would train in necessarily, I don't think, but it became its own field. Yeah, disaster psychiatry. But I just knew that something was changing. was not, all of this sort of sense of feeling torn about wanting to have more time with my kids was just, it had been rumbling in the back of my head, but it was screaming at me while that was happening.

15:33

It was the beginning of saying goodbye to this specialty and this career and this practice that I had devoted really my life to. not, know, at the time my husband was also not sure that he was in the job he wanted to be in for the long term. The challenge for us was that we were living in a situation where we needed both of our incomes.

16:02

It just sort of became, we started to look for other opportunities for him and prioritized the possibility that I might be able to take some time without working. Yeah. So this was like a unlocking of realizing that maybe anything could happen at any moment and I need to like do the things that my heart is drawn towards kind of moment for you. Cause I mean,

16:31

For someone that has your whole life, as you're a kid, you're working towards this big thing, and then to let it go seems pretty big. Seems extreme, yeah. Well, it doesn't seem extreme necessarily because I don't know if you felt, when you pursued, it sounds like you were really interested in science and you really wanted to be a doctor. Yeah, and I loved medical school. Yeah.

16:55

So it wasn't anything where you were kind of checking boxes and you figured once you hit this, you would be happy, because that's what I did. Like, I mean, mine probably stems from abandonment of my mom dying and me feeling like I needed to be perfect. And so I just needed to do everything that society told me I needed to do, never finding that happiness piece. So that's where that question comes from. But it sounds like this was your passion all along. 100%. Yeah, I was doing...

17:24

I was doing what I loved. there were, I wasn't loving it. Like I loved it. I loved it when I was in medical school and when I was in training, I wasn't loving it. I wasn't loving it after my kids were born. I mean, really that's sort of why it just, yeah, because it just, I was not feeling, I was just losing some of that passion for it because I had this thing that was so huge pulling me. Some of that come from knowing how much your kids like,

17:52

as a psychologist or a psychiatrist, you know, like the human development and how much your kids like will need you. Like, I feel like there would be that pull of like, oh, wow, I really, can't, I can't shrink on this side because they need it to become full form humans. Yeah. Yeah. I mean, I believe there are, you know, children are raised in homes where parents, both parents work, you know,

18:21

throughout history and I mean, it's more common than not. So, and they're beautifully raised and have, you know, it really isn't a question. I wasn't questioning whether or not my kids were gonna be okay. I did recognize their need for me and how much they liked when I was with them versus, you know, having to say goodbye.

18:46

And yeah, and I wanted them to be raised in a certain way that where I had more where I was much more active and present. But the thing is that what's significant to me about this, I mean, so I've so I ended up we moved to Columbus, Ohio, because my husband, he found, you know, a great opportunity. And it allowed me to take a break. I also made the decision to not network a whole lot. I did get my license in Ohio, but I didn't my medical license, but I didn't.

19:16

look for any kind of work. didn't look for any part-time work and I didn't do a lot of networking. And mind you, child psychiatry in particular, but psychiatry in general, in huge demand. mean, every day I was being asked, when are you going back to work? By people I, you know, I barely knew. But another huge thing drew me to being in Ohio, which is that my mom lived here.

19:41

And I was feeling this draw to be, I had left home for college and had never lived in the same place where she was. And she had moved to the area. I had been raised in South Carolina. She lived there until she moved to Ohio. She moved to Ohio because we have a family business in Ohio. And I was familiar with Ohio because of, Columbus because of that too. But fast forward a lot of years, I've really come to understand this decision that was a, I mean,

20:11

You talk about the life shift and how this pivotal moment changes your life forever. And there's no question that that moment of seeing those towers come down and the decision that, and knowing that things were going to change forever in my life, that I was giving something that I had devoted my life to up. I have, I think about it every day, but I think about it differently now because of the work that I did that led to my book.

20:40

And so I'll go back a little bit. So this ends up being a multi-generational situation. In 1960, my mom was 14 years old living in Columbus, Ohio, and her parents boarded a plane from Columbus to New York City that collided with another jet and everyone was killed, including my grandparents. Again, my mom was 14. They were traveling to New York for meetings to place the

21:09

family's magazine, the business, their magazine on the newsstands. And that magazine was highlights for children. Wow. The children's magazine. Yeah. So my mom's my favorite waiting room. Exactly. And as a kid, there's some dentist offices. Yeah. And we're still around. We're still around. Uh, almost 80 years old, six generations of family members. And so my book is about the experience of being raised by a mother and protracted mourning.

21:39

having lost her parents at 14, she was the second oldest. There were five kids and they were all moved to, they moved to Austin, Texas to live with their paternal uncle and aunt and then their family. Minds me of your story, you know, losing a parent so young and just having, you know, it was in December. they...

22:05

A couple of the kids finished school in Columbus, but my mom and a couple kids just middle of the year went to Texas. 14 years old. He said protracted. Protracted morning. So what I mean by that is I grew up with a mom who would get upset, start crying every time I raised the topic of these grandparents that I didn't know or other topics.

22:32

I didn't, so I grew up in an environment where I had a mother who was struggling and had not healed from her grief. ah I mean, heal from grief, that doesn't really, I mean, had not processed her grief. And I was a little kid. So that's what my book is about. It's also the story of my getting to know my grandmother through her letters. But it's become really clear to me, because as I was reading, as I was writing the book, you know,

23:01

I say that this, learned, so I also, I was raised in silence and I didn't know about the accident. didn't know, I knew that they had died in an airplane accident, but I didn't know details. And it took until I was, you know, we had, we were living in Columbus eight years almost before I realized I could research it on the internet. It was like, you know, this blinder that just lifted and I've researched it and discovered, and then

23:31

And 2010, there was a 50th anniversary memorial event in Brooklyn for the airplane accident victims. And so I attended that alone. And that was the beginning of my having a deeper understanding of what had happened and the beginning of my writing the book, which is why I say it was 14 years. It started back. I started writing and, you know, just after going to that memorial event. And but. It now I think about 9 11.

24:01

and my grandparents' airplane accident, same city, same sky, same shock. And it makes perfect sense to me that as I was watching this happen on TV, I had no consciousness of it, but I was like, I'm done. Like this can change a life and I have to live my life as if.

24:31

Each each day I need to do what I need to do and not feel torn. So that's where that that's why I feel like it's a life shift. The 9 11 event and making that decision was so, so huge. But it was propelled by something I didn't even realize at that time. Deep seated. Right. Family drama. Right. And and or trauma, I should say. Yeah. I I I write, what I talk about

25:01

in the book about multi-generational trauma is just that, my mom, as you said, silence, people weren't talking in the late eighties. They weren't talking about death, grief. Not in the sixties? They weren't talking about it. Honestly, maybe they started in the seventies, but the 20th century was a century of silence when it comes and it was a century of a lot of trauma. Probably because of the silence. 100%.

25:29

But the silence served its purpose because people had to soldier on and move forward. I have ancestors who in like 1860, they lost five children in 11 days to diphtheria. And I think the loss of children sort of in many ways to epidemics and the loss of young men in world wars and just

25:59

The loss of women in childbirth, mothers in childbirth, it's just, uh we have trauma now, it's a different, we don't have that level. And I think what people, I think human beings have just in many ways managed through soldiering on. And in fact, that family that lost all those children.

26:24

then had another batch of children, like four more children. And one of those children was the grandmother of my great-grandmother that was the mother of my grandfather that died in the airplane accident. And her raise, the way she was raised, very likely in silence around these children that had died, then responded to the loss of her son and daughter-in-law.

26:51

through silence, my mom and her siblings never heard her parents' names again. Yeah. So, or they, you know, not in any kind of significant way. Then I realized while writing the book was that actually, because part of it, you know, I was always kind of em challenged by this question of, like, how can I have this thing be affecting me so much when I wasn't born and I didn't experience it? And I definitely had

27:20

my own my experience with my mom, but then I realized actually, I did experience the silence in the same way. And that therefore I kind of come by my own grief, honestly, because I so. But I don't think you have to qualify that either. I think that is yours to hold. And and I mean, growing up with a parent like that, I can imagine is quite challenging.

27:47

as much as you want to love her, you also feel like you don't know all of it and you don't have that element. Do you feel like any of that pushed you to the career you wanted to have because you wanted to understand? Like what's happening? Yes. And when you say like, you know, I didn't understand and I also was so driven to protect that even even though I didn't know what was going on, I was very protective of my mother because she was she was your mother struggling. Yeah. And my mother.

28:17

Right. So is this why I pursued psychiatry? I would say that the real reason that I pursued psychiatry came more consciously from the trauma I experienced from my parents' divorce. That was more of my trauma. I saw a psychiatrist as a child, even though we didn't, you know, there wasn't much talk. My mom still knew well enough that her kids would benefit from talking to somebody. So.

28:45

I loved what he did and that's what made me think that I wanted to do that too. And he told me I would be good at it and so I thought, well, and I don't know, 14 years old, started my Psychology Today magazine subscription and just started like having that mindset. for me, but...

29:08

Subconsciously would it have been because I had a mom who was, know, really what it ends up being is post-traumatic stress disorder. That's what's clear. She experienced and she still does. I'm sure in some subconscious way it did influence my choice, but you know, I'm just a sensitive, you know, person always curious about other people's thoughts and feelings. also saw the modeling of like a good experience in which

29:35

think that helps. Sometimes it's like one or the other. But it sounds like maybe you had a little bit a little mix of both. Right. I always curious and this might be a totally inappropriate question. But did you ever try to with all your education and experience and all the things try to help your mother in ways or do you just be like, mean as an adult as a psychiatrist? Yeah. You mean? Or is that like a no, no, no, no, no, I mean, I wouldn't like, you know, hey, mom, need to

30:03

Can I prescribe juice? I mean, no. Because I feel like as humans, we're like, some of us want to really help. want to be maybe a tiny little savior complex of the people we love a lot. And I would imagine with all the tools you had, it would almost be like, let me help, let me do this. But maybe you didn't have those feelings. think it's not it wouldn't if I did it wasn't a conscious thought like I let me help. you know, from my I mean, I certainly

30:33

as I learned, might have told her about some things I learned and to help her maybe understand herself or me understand myself better. But the helping was always part, because it was always a situation where I was wanting to be helpful. I also still to this day, get a little tightened and hold my fist when she starts to cry. It's still very ingrained in me. uh

31:03

that this feeling that I've had since I can even remember of just like not wanting this because you don't know what's, you you want your parents to be okay and you want them. So as a child for sure, as anytime, but, I will say my mom, you know, now we cry together. I mean, it's not the same at all. can, you know, but, but still I feel that a little bit inside that same feeling. Yeah. Different to like your mom.

31:33

as a mom when you're younger, think a parent innately doesn't want to show the word is not correct, but like a weakness to their child, like they can't handle it. They need to be the bigger person, right? I feel like my dad probably did that after my mom died of just like, we're just gonna truck forward and we're gonna do this. And did he break down behind the door? You know, probably, but he probably didn't want me to see it. Want you to see it. But also like all of our...

32:03

Like all of us we were all kids like your dad was a child who didn't like to see adults cry So he knew that as an adult and didn't want you to have to see him cry That's what I imagined too. Like I know that I try not to break down into tears with little kids because I you know, cuz I know what that feels like right so Interesting. Yeah, it is interesting. It is interesting. Yeah, Well, you also you were on the phone with your mother when that

32:33

on September 11th, all that stuff was happening? My mother-in-law. Oh, OK. was going to say that might have been a totally different conversation. Yeah. No, when air disasters have happened over my adult life and her, know, and we have connected about it, for the most part, she can't talk about it when it's, know. Well, I'm curious. So you.

33:00

live in this life, this kind of like want to be full time or want to be around your kids as much as possible. Love this career. But don't love this job or whatever, but just love the the field and whatnot. You see this tragedy unfold, you realize, okay, I need to do something about this, you guys kind of take action. How do you how did you start showing up in in the world differently? Like, did you lean into things that you maybe wouldn't have done before because they weren't?

33:30

on a particular path? Like once you got settled in Ohio, what did that look like for you? It was a new world because the role of a mental health professional in general, psychiatrist in the way I was trained, it's harder to just be a regular old person in the community. In many ways, it's important to be more anonymous because you're working with people and part of working with people is not necessarily having people

33:59

be able to know everything about you and see your everyday life. So that's a challenge for people in this field. And I just felt like, you know, it was like a whole new world of being able to walk my kids to school and meet up with all the parents. And I did, many people knew that I, my background and my training, and I was happy to share it. And if people wanted to talk about their kids, you know, I called it curbside, just a curbside eval.

34:28

But I was not practicing, I was not treating, I was not, and it was very freeing. That was particularly with having little kids. Showing up like a human. Not that you weren't a human before, but like being able to show up as a mom and mom first. Exactly, exactly. It's different. And that was also part of what I was letting go of as some of that restrictive, the restrictions that I was feeling in Albany of just sort of not being able to.

34:59

just be a regular person in the community. Was there an element of leaving it behind that was kind of like hard? I mean, if you spend so much time building it out. my identity. Yeah. What does that feel like? um

35:15

It was really hard. It was every single day in my head, back like a ping pong ball over and over and over. What do I do? What do I do? Do I go back? Do I stay? Do I keep doing this? Every year it would be a new time to make a new decision. There were some job opportunities that presented themselves or I would talk to somebody in the field locally and...

35:42

and think about ways that I might get, know, and people would say, just hang a shingle and you'll be booked immediately, you know. And I knew that to be true. And over time, it started to, some of it started to relax. I got involved and I served on community boards. I'm involved in highlights, which is the headquarters are here in Columbus.

36:06

really involved in my kids' lives and there very many activities and all of the things that occupied that. But it was daily. it's aside from, mean, you do reach an age when it is sort of hard to go back. And now I'm 20 years, 20 years out. I mean, I could go back. I have a license. The one thing that would be a struggle was getting board certified again. I would have to sit and...

36:35

But I you know, I renewed the license every year but every two years but um I'm not board certified and and and and the main thing is that I Decided so I started taking some classes. I'm creative writing. Okay, I started some other yeah and I did have that drive to do that and because you know that was sort of finding that part of me that loved doing that writing as a kid and you know high school college I always was writing and then I

37:05

took some classes at Ohio State. And then during the pandemic, I decided to go back and get my MFA in writing in creative nonfiction. And that's when I was able to take on writing my book. and so I have a new sort of feel like I have a new place now where I can, and it's actually kind of perfect because my training in psychiatry informs memoir as a writing. mean, it informs, it informs everything.

37:33

about me. I mean, it's a huge part of who I am. Unfortunate as well. It can have its drawbacks, but it's just it is who I am. Like when I say I'm a retired psychiatrist, it's just never I'm never not going to be. I'm never not going to be a doctor. It's just something I have as part of my existence. But I also now have this degree in writing and the ability to help other people and training to be a book coach and help. I love the idea of helping people tell their stories in creative ways.

38:03

kind of like your other job. Yeah, exactly. It feels very, it feels like it's a perfect sort of melding. I love that. Like, I don't know. You mentioned there's a certain point in life where you it's too late or not too late, but it's hard to turn the corner. Right. But like you created something new, like a new version or you kind of built upon

38:27

Like you built a lot, there was a lot next door and like you built a house on the lot next door so you can still see your old life and all the things. Yeah. They're like during the pandemic. I got a second master's degree because I was bored. Not any other reason, but the podcast came out of it. And you know, I don't think it would have happened. So my question really is did the memoir spark

38:52

Did the idea of a memoir spark you to take the classes to get the degree or did it become a byproduct of taking those classes and get the degree? So I wrote after I attended the 50th Memorial in 2010, I wrote a sort of an essay about the experience. It was my first time writing about my grandparents, about the airplane accident. And I

39:17

So I wrote like it's like a 40 page essay about the experience of attending the memorial and then sort of going back into the story and then I start I enrolled at a workshop a couple workshops at Ohio State and I shared that essay with the class it was then that the professor gave me some feedback at the end of the semester and told me that he thought I was writing a book and my reaction to that was that I I took his feedback and

39:47

and the class's feedback, which was all a pile of papers, because it wasn't all online at that point. And I went home and I shoved it into a cabinet and I didn't open it for 10 years because I did not want to write a book about this. It was painful to write that essay. I wanted to close the store. think that, you know, I'm a kind people who write, people who like to talk about stories are finding ways to process painful parts of their lives.

40:16

I wanted to have checked that box with the essay because I couldn't go deeper. But then in that next decade, the teens, my mom became the um archivist and the historian at Highlights and started to accumulate. I asked her if there were any letters of my grandmothers to send them to me. And then I accumulated all these letters over time. And then with the pandemic, I had this essay, I had these letters and I knew I had a book. But, ah and that's when I said, okay, I'll do this, but.

40:45

It was weighing on me for a really long time. that was, that as I started was the kickoff. Yeah. Yeah. What was it like when you first sat down after like those 10 years to try to like, cause you were pushing it away for 10 years because it was going to be hard. Was it as hard as you anticipated? It was incredibly hard. Yes. It took over my life for those years of writing.

41:14

I had to put my entire whole self into the whole process. I had to give myself over to it, let myself be as vulnerable in the processes I could, did a lot of processing with my mom, read thousands of pages of letters, and just would get up at 2 a.m. and just write in the dark and just whatever came out.

41:40

figuring out how to put it together, the structure of it, the way it was being written. It's a lyrical book, it's experimental, it's hybrid. There's all sorts of stuff in it. There's some poetry, there's even some fiction, because it just had to become what it was going to be. I had to process anger, I had to process sadness, but I came from it. I came at it from a place of love. That saved me. That was a sort guardrails for it, because if I really had...

42:08

came from a place of love, could tackle it the way I needed to in a way that felt right and good. It was really hard. I always tell writers when they're working on something that's really, really hard and really like taking them down, have something they're working on. Have something to work on that's light. It's little. So the pandemic, was like fighting with this chipmunk in my garden because he was trying to, you know, take over a little section of the bed. And I was like writing about the chipmunk because it was cute and fun. uh

42:37

And that's, I mean, that kind of stuff like pulls you through. Yeah. No, I mean, but it's important. I feel like so much of my growth has come from like facing the hard things and processing them. So I can imagine when you were done. That probably felt like weird because you had processed so much and you felt it was hallelujah. It was such it was yes. Did you feel different? Yes.

43:06

100%. 100%. I saw all of it in a totally different light. And a large part of that was going through my grandmother's letters and meeting her and finding her. I was named for her. So I discovered her. I met her and I engaged with her in conversation, which is in the book. That was like, just have now I have a relationship I didn't have before. And fascinating.

43:32

Isn't that it's really something yeah to me to feel like you knew someone that will that passed before you were born. Right. And you didn't really hear a lot of stories growing up about her right. A few but nothing. Yeah I mean I had a sense of her but not like I knew her. And that came through writing like that came through writing as if we were having a conversation. And that was just lifted a weight. And you know uh I mean.

44:00

I had to go through a lot, but yes, I felt very different, very changed and wouldn't trade it for anything. Would not trade it for anything. I think it's I think it's important. I think it's lovely. I think however we can get our stories out and you know this from a professional standpoint of hearing people's stories, but now you got to be be the person dumping in front of you, which was probably a totally interesting experience. But what I've found is the more that

44:31

I say my whatever's out loud, the less messy it is in my head. I've always described it, not always, recently I've described this as like in my head in a situation, whatever I'm facing, it's like papers are flying around everywhere. I say it out loud and it becomes just like a stack of papers that I can easily like filter through. And I'm like, but it's the same information that was up there as it is out here. And it just makes more sense when I say it out loud. So I can imagine.

45:01

what going through that process as hard as it would be and then literally putting it in words in an order was probably quite healing in a way that you were very scared of for 10 years, I guess. Yeah, for sure. It was like a puzzle that I didn't want to try to attempt to do until I could. And then and then that puzzle became became just a lot of sticky notes with words with.

45:30

themes and titles. And then I took the sticky notes and started to put them in some order and wrote to each sticky note and then was able to find a book in there. Has your mom read the book? She has. She was one of the first readers. She couldn't write. She didn't read it while I was writing it. She didn't feel she could. yeah, she loves it. It's not easy. know, it's not easy for her to read.

46:00

But she's my biggest cheerleader around, you know, around writing and particularly around this topic and has always supported me, didn't put any restrictions on what I would do. And I think feels, I think feels some pride in it, especially knowing that her mom's voice has been lifted from the letters, you know, her story and my story, that they have the potential to make a difference. And as I was mentioning before, like how, you know, I was a little surprised by what people are most struck by, because there are a couple of things in my book that are like hooks.

46:30

highlights the airplane accident. It was a famous, it was the largest commercial jet accident up till that time. was famous accident. What people are really, really connecting to is that it's making them think of their own stories, their own ancestral stories. What, you know, thinking about, I mean, everything, know, grandmothers dying in childbirth and, you know, losing siblings and...

46:59

in wars and sudden accidents. I just I'm hearing I hear so much. And it's just an honor to hear these stories and to feel like I'm doing even the smallest part of helping people think through and process what's happened for them. It's it's even though that's your gift. Yes, doing it. It's just coming full circle. Yeah. No, think it's beautiful. I think I you know, it's funny, I hear something

47:27

on a lower, smaller scale, but as part of the kind of guest pitch process for the show, I always kind of push back to the guests of like, you identify a very specific life shift moment in which you really feel that kind of everything changed in you? And I've heard many times from guests of like, I love that exercise, because sometimes we're like, oh, was like for me when I first started the show, was like, oh, it was when my mom died. But it

47:56

actually was when my dad said the words to me, which was hours later. And so to narrow it down to like, because I was still living life, she was gone. Life was normal for me until I found out. So it's been a really it's like a similar thing of people like, yeah, I've never like, pinned it down to when I flipped the page in this book. And I these three words. Yeah, know, life, life changed for me, which is yes, so cool. And so fun. So cool. Weird. Yes, for sure.

48:25

Yes. No, I love it. And it just tells, you know, like these these human stories are just so important to share. learned about through this podcast, like epigenetics, which sounds like very much like an understanding that, you know, our ancestors may have had these experiences and perhaps some of that is transferred through our DNA and we absorb it. Totally. In some way. So that's right. That's totally it's a real thing.

48:55

Multi-generational trauma is real. Yeah. That's not a question. And the other thing that I can say from this experience and in retrospect, just about my sort of how I perceive my life shift moment is that everybody is allowed to change their mind. Were you allowed to change your mind? I did not believe that I should be stopping something that I had put my entire life into.

49:24

And to think that I would give it all up. yet it's big. And yet I've, I have said since that day or since, since the moment that I realized that I was doing it, everybody has the right to change their mind. Yeah. And it doesn't matter your age. Yeah. It doesn't matter your age. doesn't matter what's gone into it. It doesn't matter if you've got in my case, a hundred thousand dollars in debt. mean, you know, from medical school, it doesn't matter.

49:52

everybody has the right to change their mind because everybody's life, you have to have some control over where things go. And everybody's got one life, you know, got to live it the way we know it's to be lived. Yeah, that's true. We know for me and this was maybe something similar to maybe how your mom felt. mean, for me, growing up, my mom was 32 when she died and I just never pictured a life after 32. Like I just thought

50:22

So like I didn't have any plans for when I turned 33, because I just never thought it was a possible thing, even though everyone around me was old. Like my dad got old and, like everyone else was getting older. But in my mind, I was stuck there. And so you're right. Like we don't know. Well, first of all, we don't know when our last day is going to be. And it could happen suddenly, like all the people on September 11th, like your grandparents and the people that they were sitting around. And so, yeah, change your mind all the time.

50:52

As long as you're not hurting someone with your decisions, I feel like this is your life. Do what you want with it. And that's right. Yeah. But I love the idea. Like now I'm picturing the house that you built next to the house you already had of like, love that. But you know, it's a great metaphor. Yeah. Because you found a space in which all the things that you loved and you loved learning about other people you can now use not only in your own memoir, but like helping other people. Right. Like so.

51:22

It's just a nice little like side road that you took. Right. Exactly. I came. It is. I came. I came back around to the same work that I that that's the same part of the work that I was doing. I came back around to a helping part that I loved. And yeah, that's that's exciting. And and and you know, it's it's it's part of that continual discovery that that shouldn't end for people in their lives. Maybe I'll make a big life shift.

51:50

decision tomorrow. Who knows? Who knows? Yeah, and we shouldn't we don't need to plan. can just figure it out. As we go. right. That's right. I'm wondering if like 2025 Marty if you could if you could walk into the bedroom where you're watching that television that day on September 11 before everything started crashing down. Is there anything that you would want to like whisper in her ear or tell her about this journey she's about to go on?

52:18

ah I would tell her that thing about how you have the right to change your mind. That it's okay to let something go that you thought was never going to be allowed to be let go. And that's okay. And also I would say, listen to your heart, listen to the voice inside. Don't let all of that stuff

52:47

that's crowding out that deep voice, silence it. If you have something that's really talking to you that's inside, just listen to it and let it have oxygen too. We're not trained to do that. Really. It feels like we're just taught. Like school teaches us to define the track and... We're taught to be on trajectories.

53:13

I think that that's changing some. think younger people realize that you can have multiple careers over time or, you know, switch things out. But my parents' generation, my generation, it's not as typical. We are taught to go on trajectories, let them play out, and then don't disrupt them. Yeah. And then retire. And then retire, if you can. If you can. Well, back then.

53:44

Right. I mean, that's what we came from. Yeah. So that's what I would tell her is that you can change your mind and listen to that. Yeah. And you're going to be getting another master's degree or you're going to be getting a master's degree in fine arts. So get ready. Yeah. Yeah. No, don't know that I would have at that point. I don't think I would have thought that that was a something happening. But but but you never know how life unfolds. love it. So

54:12

two things. First, if people want to learn more about your book, connect with you. What's the best way to find you in your book? Tell us more about that. So Marty Ross Dolan on Facebook, Marty Ross Dolan on Instagram, and my website, MartyRossDolan.com. And it's Marty with a Y, Dolan with an E. And those are all ways to be able to access. My book is always there.

54:41

Always Gone, A Daughter's Search for Truth. It's out there. It was released in May. Awesome. So it's out in the world. Yeah, we'll definitely put the links to your socials to connect with you and your website and a link to your book, which I'm assuming is on your website, just so people can access it pretty easily. I'd also encourage anyone that listens to your story, maybe connects with a certain part of your story. I would encourage them to reach out to you and bug you and say, hey,

55:08

this part of your story really connected with me. Here's why here's my story because I really truly believe in the power of telling our stories. So if people have these opportunities to reach out, I hope they will. And I hope you don't mind that I just told them. No, not at all. I mentioned it like it's such an honor. I feel so I feel just it's just a gift to me to know that people are feeling touched by this and that it's it's moving them further in their own stories to. Yeah.

55:37

Well, I appreciate you sharing your story in this way on the life shift, your story in the book, in the way that you did. And I hope that people will continue listening to this episode and to read your book because I think there's just so much humanity in getting these stories out there and they'll be out there forever now. And your grandmother's, you know, you and your grandmother's relationship through your book is going to be out there. Yeah, that's beautiful. Yeah.

56:05

Yeah, thank you. Thank you, Matt. And I just have to say the work that you're doing is tremendous. And so thank you for that, too. I'm delighted to be here. So thank you. Well, I appreciate that. And the eight-year-old version of me is walking beside me and getting the healing that he needed at the time. And I'm super honored to be able to hold these conversations and talk to people like you that maybe I never would have bumped into in the world. so...

56:31

Thank you for reaching out and connecting. And I just want to say thank you to all the listeners for just being on this. However long this journey goes, I'm here for it. We're over 200 episodes now. So thanks for being a part of this, And I will be back with a brand new episode. again. Yeah, thank you.

57:00

For more information, please visit www.thelifeshiftpodcast.com